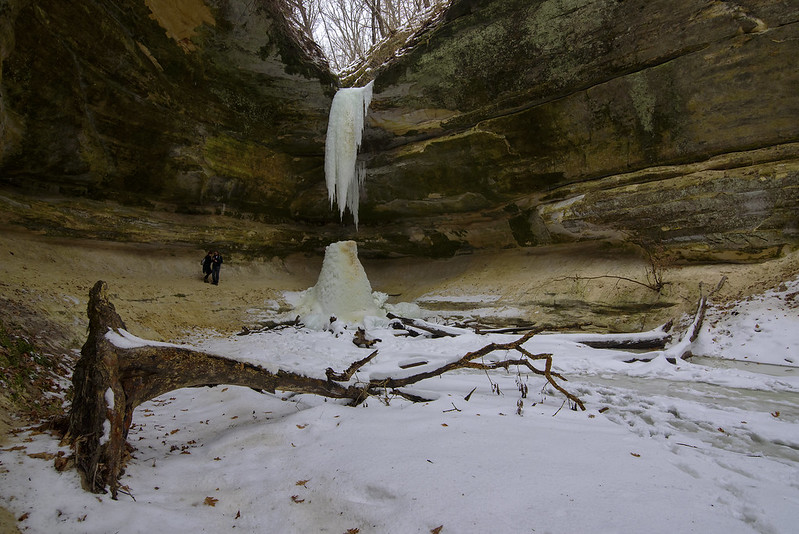

A 60 degree difference between last Wednesday and this Sunday allowed us to explore more of Starved Rock State Park's frozen waterfalls. Low temperatures of -24 F helped freeze the waterfalls solid in just a few days. Today's temperatures in the 40s began the melting process, but the cool canyons still retained most of their ice.

An unusual sight for me was the white frost on the walls of Tonti Canyon. I think it is due to the very cold temperatures a few days ago, then the warm temps yesterday and today. The warm air condensed on the cold canyon walls, and created frost. It certainly gave the canyons another layer of contrast.

In just a week's time, the main waterfall in Tonti Canyon completely froze from top to bottom. Take a look at

this post to see what the waterfall looked like last week. I'd estimate the height of the waterfall at around 60 feet, and if the cold comes back soon, this icefall will continue to build in thickness and perhaps allow ice climbers a chance at tackling the difficult climb to the top.

While being careful of the hanging icicles above, we wandered behind the icefall for a view of the backside. Unlike the thinner ice columns of LaSalle Canyon, this ice isn't as transparent, but it does offer a look at the beautiful details and patterns in the ice.

Looking closely to the left of the ice column, you can spot the second icefall of Tonti, a bit smaller, and not yet connected from top to bottom.

The Tonti Canyon bridge has been closed for quite some time, forcing visitors to take a 15 minute detour back through LaSalle Canyon. It's never a bad thing to visit this canyon twice in an afternoon, but the longer hike takes some time away from exploring other canyons along the way. I'm not sure what the State is waiting for - the bridge can be repaired for very little money, and very little time. Unless the bridge isn't the problem, perhaps it's the trail itself which seems a bit narrow just before the bridge. Either way, it's time something is done to improve a beautiful trail in Illinois' second largest attraction.

The sky and sunlight changed as fast as the winds blew on this stormy February afternoon. Wind gusts over 50 MPH created plenty of drama in the sky as well as on the water, with waves crashing into the shelf ice, shore, and pier of South Haven, Michigan. Happening in mid winter when the shore is mostly lined with mounds of shelf ice, beach erosion is actually kept to a minimum because the shore is buffered by the ice formations. In warmer periods, a good portion of the beach can erode away in just one day. As the sun poked through the heavy clouds, it highlighted the ice, water, lighthouse, and splashes on the pier, providing a great contrast against the cold snow and ice.

The sky and sunlight changed as fast as the winds blew on this stormy February afternoon. Wind gusts over 50 MPH created plenty of drama in the sky as well as on the water, with waves crashing into the shelf ice, shore, and pier of South Haven, Michigan. Happening in mid winter when the shore is mostly lined with mounds of shelf ice, beach erosion is actually kept to a minimum because the shore is buffered by the ice formations. In warmer periods, a good portion of the beach can erode away in just one day. As the sun poked through the heavy clouds, it highlighted the ice, water, lighthouse, and splashes on the pier, providing a great contrast against the cold snow and ice.  Stepping back to take in more of the pier, and using a wider lens, more of the dramatic sky could be seen behind the pier and lighthouse. The beach parking area was quite crowded with spectators out photographing the waves. Most did not venture out of their cars, but those who did, got to experience intense wind gusts exceeding 50 MPH. Sand, acting more like a light snow, was blown from the beach down the nearby streets where it collected along the curbs and in every place exposed - including my ears!

Stepping back to take in more of the pier, and using a wider lens, more of the dramatic sky could be seen behind the pier and lighthouse. The beach parking area was quite crowded with spectators out photographing the waves. Most did not venture out of their cars, but those who did, got to experience intense wind gusts exceeding 50 MPH. Sand, acting more like a light snow, was blown from the beach down the nearby streets where it collected along the curbs and in every place exposed - including my ears!